What Is the Nurse's Responsibility When Ebp and Patient and Family Practice Do Not Match?

- Inquiry article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Bear witness based practice beliefs and implementation amidst nurses: a cross-exclusive study

BMC Nursing volume thirteen, Article number:eight (2014) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Having a positive attitude towards bear witness-based practice and beingness able to meet the value of evidence-based practice for patients take been reported as important for the implementation of evidence-based practice amid nurses.

The aim of this study was to map cocky-reported beliefs towards EBP and EBP implementation among nurses, and to investigate whether there was a positive correlation between EBP behavior and EBP implementation.

Method

We carried out a cross-sectional written report among 356 nurses at a specialist infirmary for the handling of cancer in Kingdom of norway. The Norwegian translations of the Evidence-based Exercise Belief Calibration and the Evidence-based Do Implementation Scale were used.

Results

In full, 185 nurses participated in the study (response rate 52%). The results showed that nurses were positive towards evidence-based practice, simply only practised it to a small extent. There was a positive correlation (r) betwixt beliefs towards evidence-based exercise and implementation of prove-based practice (r = 0.59, p = 0.001).

There was a statistical significant positive, simply moderate correlation between all the four subscales of the EBP Beliefs Scale (behavior related to: 1) knowledge, 2) resources, 3) the value of EBP and four) difficulty and time) and the EBP Implementation Scale, with the highest correlation observed for beliefs related to knowledge (r = 0.38, p < .0001). Participants who had learned about evidence-based practice had significantly college scores on the Evidence-based Do Belief Scale than participants who were unfamiliar with evidence-based practice. Those involved in evidence-based exercise working groups likewise reported significantly higher scores on the Evidence-based Practice Belief Scale than participants not involved in these groups.

Conclusion

This study shows that nurses have a positive attitude towards evidence-based practice, but practise information technology to a lesser extent. At that place was a positive correlation between beliefs about evidence-based practice and implementation of evidence-based practice. Beliefs related to knowledge appear to have the greatest effect on implementation of evidence-based practise. Having knowledge and taking part in evidence-based do working groups seem important.

Groundwork

Internationally, evidence-based practice (EBP) has been a priority for many years. Both the World Health Organization and the European Commission emphasize that health and social services should exist based on the all-time research evidence [1]. EBP is an approach that requires that decisions about wellness care should be based on the best available, electric current, valid and relevant evidence [two, 3]. In addition, evidence-based decisions should be made past those receiving care, informed by the tacit and explicit knowledge of those providing care, within the context of available resource [iii]. EBP involves the following steps: asking clinical questions, searching for and collecting the most relevant best evidence, critically appraising the testify, integrating the evidence with one's clinical expertise, patient preferences and values, and evaluating outcomes of the practice decision or change fabricated on the evidence [four]. EBP implementation involves use of the EBP steps and strategies that promote integration of best available evidence with practitioner expertise and other recourses [v].

Finding, appraising, applying and evaluating research evidence are essential components of EBP. However, earlier studies show that nurses seldom incorporate research findings into their practice, and they tend to use knowledge derived from experience and social interactions [six–10]. These results hold with findings from surveys among Norwegian nurses [11, 12]. Results from these studies prove that nurse practitioners rarely use research and rely on other sources of information such as: their ain and their colleagues' practical knowledge, knowledge gained from their nursing education, nursing literature and guidance from experts [11, 12].

Contempo studies from various countries take reported that nurses use EBP to a limited extent [13–16]. Well documented barriers, such as lack of time to read literature and lack of authorization to change practice, have repeatedly been found to hinder use of EBP among nurses [14, 17, 18]. Organizational barriers include lack of staff experienced in EBP, supportive leadership and lack of resources [18, 19]. The many identified barriers towards EBP are not surprising considering that EBP is a procedure that is far from straightforward and does not follow a prescribed, logical and linear path, but is both challenging and circuitous [xx, 21].

Despite these barriers, nurses more often than not report positive attitudes and behavior towards EBP and they recognize the importance of EBP for quality of intendance – this is independent of workplace, part, or nationality [22–26]. Findings from previous studies indicate that nurses' attitudes and beliefs are associated with the extent to which EBP is implemented [16, 27–31]. Consequently, attitudes and beliefs tin potentially predict futurity behaviour [32].

EBP is rather a new concept in Norway and little is known near EBP behavior and utilise of EBP among Norwegian nurses. In this study, we aim to explore EBP beliefs and EBP implementation among nurses in a university hospital setting, and to investigate whether in that location was a positive correlation between EBP beliefs and EBP implementation.

Methods

Participants

A descriptive comparative study design was used with a cross-sectional sampling among nurses at a specialist university hospital for the treatment of cancer. The hospital aims to implement EBP in nursing care.

The Norwegian nursing didactics is a 3-years bachelor programme (180 ECTS) [33]. Farther in the article we refer to them as registered nurses (RN). Nurses take the opportunity to conduct specialization after having gained some clinical experience for some years. Education which provides specialist expertise in nursing is done by universities and university colleges and leads in some cases to a master'south degree. The program takes from ane to 2 years fulltime (referred as specialist nurses) [33]. Nosotros also included the nurses that were not ever straight involved in patient care, such equally senior accuse nurses and professional development nurses at the hospital units, as support from nursing administrators and leaders, is seen every bit a cardinal element to promote EBP [34].

Participants were nurses who were at work at the hospital between September 20th and December sixth 2010 (due north = 356). Ane of the questionnaires asked virtually EBP activities done during the by eight weeks. Exclusion criteria were, therefore, nurses who had not been at work during the previous 8 weeks (n = 2).

Measures

Nosotros used the Norwegian translations (unpublished) of the EBP Beliefs Scale and the EBP Implementation Scale developed by Melnyk and Fineout–Overholt [35]. The EBP Beliefs Scale and the EBP Implementation Scale accept been used and tested for reliability and validity in several studies among nurses [5, 35–44]. In addition, demographic data were nerveless related to: historic period, seniority, chore position, pct of total-time position, didactics, and participation in prove-based workgroups. We as well asked if the nurses had any previous knowledge about EBP.

To find out whether respondents were different from non-respondents, we collected background information on age and continuing education for all the nurses at the infirmary.

The EBP Beliefs Scale consists of 16 statements that allow measurement of an individual's beliefs well-nigh the value of EBP and their power to implement it [5]. In the EBP Beliefs Scale respondents are asked to score the level to which they agree or disagree with the 16 statements past answering on a v bespeak Likert–calibration that goes from strongly disagree (1) to strongly concord (5). Examples of statements are: "I believe the care that I deliver is evidence-based", "I believe that EBP results in the best clinical care for patients". The scoring on the xvi questions is added up to a minimum of 16 points and a maximum of 80. In that location are two reverse-scored items. Once reversed, all items are added to give a total score. College scores reflect more positive beliefs about EBP.

To study nurses' beliefs about EBP, we used four subscales of the EBP Beliefs Scale, defined past Estrada [38]: (1) knowledge beliefs, (2) value behavior, (3) resource beliefs, and (4) time and difficulty beliefs. Items related to knowledge beliefs consist of knowing the steps of EBP, measurement of outcomes, implementation to make practise changes and confidence (north = 5). Value items include beliefs that EBP results in the all-time clinical care and improves patient care (n = v). Included in the resources items are admission to the best resources and ability to overcome barriers (northward = 4). Time and difficulty beliefs take in items about time to do EBP and whether nurses find EBP difficult (n = 2).

The EBP Implementation Scale consists of xviii statements that allow the participants to answer to each of the statements on a 5 point frequency scale past indicating how oftentimes in the past 8 weeks they performed the item [5]. In the EBP Implementation Scale questions are linked to actual utilise of EBP in professional person performance measuring the essential components and steps of EBP, for example, how oftentimes accept yous, "critically appraised testify from a inquiry study?", or "used show to change my clinical practice. The response alternatives are 0 = "0 times", 1 = "one – 3 times", 2 = "four – 6 times", three = 6 – 8 times and iv, pregnant "> 8 times". Scoring consisted of summing responses to the 18 items for a total score that could range from 0 to 72. Higher total scores reflect more frequent use of EBP behaviours and skills [five]. Further, response alternatives for items related to EBP implementation were collapsed into iii categories, namely "0 times", "ane to five times" and "6 times or more".

Procedure

Each hospital unit of measurement assigned a contact person for the projection. The contact person and the senior charge nurse at each unit were informed nigh the aim of the report. The first writer then disseminated information about the survey to all nurses at the infirmary a week earlier the data drove started. The contact persons reminded the nurses daily about the survey. In addition, they were responsible for handing out and collecting the questionnaires, including the information letters and reply envelopes. Earlier participation, all the nurses that participated signed a written consent course after they had received an explanation about the research, the voluntary nature of their participation, and a guarantee of anonymity. The data collection took identify during a 3-calendar week catamenia from November 15thursday until December 6th 2010. Ethical and authoritative approvals were obtained from the Health Enquiry Ideals Board, Oslo University Hospital on Oct, 28th 2010 (ID #25878).

Information analysis

The IBM SPSS software Version 18.0 was used in this study.

In accordance with recommendations from Polit and Beck [45], mean substitution was used for missing information on the EBP Beliefs Scale and the EBP Implementation Scale items if less than twenty% were unanswered. Internal consistency of the scales was investigated using the Cronbach'southward α. To appraise non-response bias, demographics for the entire sampled group were collected and demographics on historic period and level of teaching among respondents and non-respondents were compared.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the background factors, besides EBP behavior and implementation of EBP.

To investigate a possible linear relationship between attitudes and EBP beliefs and implementation we used the Pearson'southward correlation coefficient (r). Partial correlation coefficients with adjustment for all background factors were also calculated.

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to make up one's mind the contribution of background variables, on EBP beliefs and implementation, respectively, while controlling for the other variables.

The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

The questionnaires were distributed to 356 nurses. In total, 187 nurses returned the questionnaires and 185 of these were included (52%). Ii of the respondents were excluded as they had answered less than lxxx% of either the EBP Beliefs or the EBP Implementation Calibration questions. In that location were no statistically pregnant differences in age or level of pedagogy between respondents and non-respondents. The internal reliabilities (Cronbach's Alpha) for this study were 0.86 for the EBP Beliefs Scale and 0.85 for the EBP Implementation Scale.

One-half the participants were employed as registered nurses with a Bachelor'due south degree (fifty.8%), while 38.9% were employed as specialist nurses. Some other 7.6% of the participants worked as senior accuse nurses and ii.7% as professional development nurses (Table 1). The majority of participants (87%) were lxxx-100% full-time employees, and a pocket-sized proportion worked 50% or less (six%). Almost all of the respondents (96.2%) had contact with patients in their daily work.

The majority of nurses (82.2%) had learned nearly EBP, and 69.seven% of these had learned near EBP through piece of work, 25.7% in their basic nurse education and 8.5% in their postal service-graduate instruction (Table 2). A total of x.eight% of the nurses said they took part in EBP working groups, where they either adult evidence-based guidelines, protocols or patient information or wrote scientific articles using EBP.

Behavior towards EBP

For the EBP Beliefs Scale, the average total score was 42.0 (possible scores xvi – eighty) (standard departure (SD) = 6.eight, range = twenty – 70). The distribution of answers inside the four subscales of the EBP Beliefs Scale is presented in Table 3. The majority of the respondents (71.8%) scored highest in the subscale «Beliefs related to the value of EBP». A total of 86% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that bear witness-based guidelines can meliorate clinical practise. Further, 79% agreed or strongly agreed that critically appraising evidence is an of import step in the EBP process and 78% agreed or strongly agreed that EBP resulted in the best clinical care for patients (Table iii). Only a few participants strongly agreed or agreed on the statements well-nigh having noesis near implementing EBP sufficient enough to make practice changes (12%), measuring outcomes of clinical exercise (13.five%), and whether they believe they can access the all-time resources in order to implement EBP (17.0%).

EBP implementation

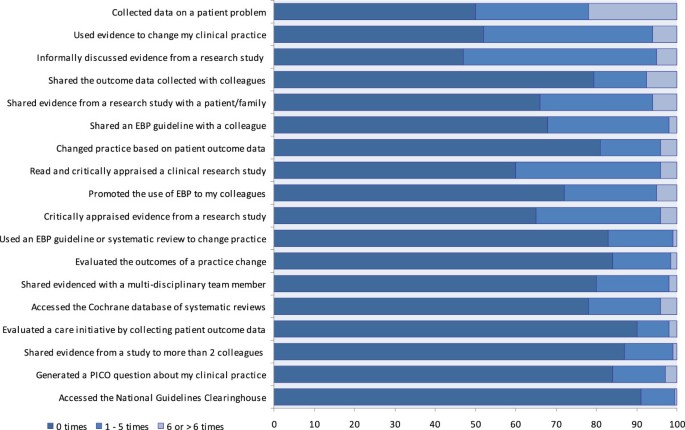

The average total score on the EBP Implementation Calibration was vii.8 (possible score 0 – 72) (SD = 7.ix, range = 0 – 48). Over half the participants (53%) answered that they had informally discussed a research study with a colleague more than in one case in the concluding 8 weeks. 40 per cent had read and critically appraised a clinical research study during the last eight weeks and 34% had shared evidence from a research study with a patient/family fellow member. Few nurses had carried out actions related to EBP (Figure 1). A total of ninety% stated that they had non evaluated their own practice systematically during the last 8 weeks (Effigy i).

Activities carried out which are asked virtually in the implementation scale.

Link between EBP beliefs and EBP implementation

There was a positive correlation betwixt the EBP Beliefs Scale and the EBP Implementation Scale (r = 0.59, p = 0.001), which indicated that the stronger beliefs a nurse has in EBP the college the nurse will study EBP implementation. This relationship was upheld afterward adjusting for all the registered background variables.

There was a statistical meaning positive, but moderate correlation betwixt all the 4 subscales of the EBP Behavior Calibration (beliefs related to: 1) knowledge, two) resource, three) the value of EBP and 4) difficulty and time) and the EBP Implementation Scale, with the highest correlation observed for beliefs related to cognition (r = .38, p < .0001) (Table 4). To investigate which background variables have an independent effect on behavior and implementation of EBP, we used multiple linear regression assay (Table 5). The analyses showed that those who had learned about EBP (B = 2.7, 95% CI = 0.2 to v.3) and those who took part in EBP working groups (B = 3.2, 95% CI = 0.i to 6.3) had statistically meaning higher boilerplate scores for behavior in EBP than those who had neither learned near EBP nor worked in EBP working groups. Registered nurses also scored significantly lower in behavior in EBP than more than highly trained nurses (B = -4.2, 95% CI = -eight.three to -0.ii). None of the background factors were associated with implementation of EBP in a statistically significant manner (Table v).

Discussion

The results showed that nurses were positive towards EBP, but merely practised EBP to a pocket-sized extent. Conventionalities in EBP was significantly higher amid those who had learned nearly EBP and those who participated in EBP workgroups. The analysis of each subscale of the EBP Belief Scale showed that our sample, to a big degree, believe in the value of EBP. However, they accept less faith in their own knowledge in relation to EBP. When it comes to behavior related to resource for EBP the nurses scored depression. About nurses in our written report "neither agree nor disagree" with the question near whether EBP is difficult and takes fourth dimension. Furthermore, in that location was a correlation between beliefs and EBP implementation.

This written report was conducted among all nurses employed at a selected infirmary, regardless of their knowledge of EBP. The average full score on the EBP Implementation Scale proved to be low compared to before studies done among nurses, using the same scale (7.8 of a possible 0 – 72) [5, 29, 39–43, 46]. Wallen, Mitchell, Melnyk et al. [43] found the highest average score on the EBP Implementation Scale (40.9 of possible 72). The respondents in this study participated in an EBP mentorship plan (northward = 54). They included nurses in management and senior positions that would lead and mentor nurses throughout the nursing department [43]. Given the high levels of competence among these participants, the loftier average score in the study is not surprising.

Despite the low boilerplate score on the EBP Implementation Calibration in our study, we saw signs of EBP implementation. For case, one-half of the participants had discussed a research article informally with a colleague during the previous 8 weeks and around a 3rd had read and critically appraised a research commodity and communicated evidence from a inquiry study to a patient/relative or told a colleague about a clinical guideline. However, hardly any of the respondents (90%, n = 167) had evaluated their own practice systematically. Consequently, this is an area that needs to be focused on in the time to come, for example by audit and feedback. Audit and feedback is widely used equally a strategy to improve professional practice either on its own or as a component of multifaceted quality improvement interventions [47].

The participants in our written report had depression scores on their behavior about resources linked to EBP. In specially, they were unsure virtually whether they had access to the best resources needed to apply EBP, although health workers in Kingdom of norway have free internet at work and free admission to scientific articles via the Norwegian Electronic Health Library [48]. Access to literature is seen as an important initiative for implementing EBP [49, l]. Several studies take pointed out that, when planning to introduce EBP, in that location must be opportunities to search for literature and to find systematic reviews and articles in total-text versions [50–52]. It may be that the participants in our study take a unlike understanding of the word "resources", but it is also possible that they are not aware of or familiar with the Norwegian Electronic Health Library.

Most nurses in our study "neither agreed nor disagreed" with the question about whether EBP is hard and takes time. A possible explanation may be that few nurses accept been involved in divers EBP activities, and therefore they had no real concept of whether or not EBP was difficult or fourth dimension-consuming. This finding differs from other studies, where nurses consistently report lack of time as a considerable bulwark, and lack of time is the nearly frequently cited barrier to use of research [53]. Daily responsibility for many patients per nurse and for avant-garde care can exist difficult to combine with carrying out EBP. On the other hand, the high workload and the level of responsibleness within nursing strengthen the need for basing practice on the best bachelor and updated evidence. Administrative support, proper planning and use of human resources are therefore essential to allow nurses to fit EBP into a busy schedule.

At that place was a positive correlation betwixt the EBP Belief Calibration and the EBP Implementation Scale, even after adjusting for groundwork variables. This may mean that the individual'south attitude to EBP is related to the extent to which they carry out EBP. If and so, time to come interventions should influence nurses' perceptions of the advantages of EBP in improving clinical care and patient outcomes. This could requite nurses more motivation to acquire virtually and appoint in testify-based work.

There was a significant correlation between all four subscales of the EBP Conventionalities Scale: (ane) knowledge behavior, (2) value beliefs, (3) resources beliefs, and (4) time and difficulty beliefs and the EBP Implementation Scale. In our report, the sample had a high level of belief in the value of EBP, simply a lower level of beliefs in their ain noesis near EBP. At the same time, beliefs nigh their own knowledge correlated most strongly with the EBP Implementation Scale. These findings seem to be consistent with the Transtheoretical Model of Organizational Change. When knowledge about EBP is adult and conviction is strengthened, the private will be motivated to go involved and work in an prove-based way [41].

Earlier studies back up the idea that attitudes towards and implementation of EBP can be influenced by education and competence building, accessible resources, making time bachelor, and use of EBP mentors who back up nurses in implementing EBP [22, 49–52, 54, 55]. Thus, nurses who have cognition and competence in EBP; admission to resource; experience support; or are active in developing evidence-based guidelines and procedures have more conventionalities in EBP.

A key question that has arisen is whether it is reasonable or achievable that every nurse should know and follow all the steps in EBP, and if it is desirable that each individual nurse is able to arrange his/her exercise on the footing of valid and relevant current research. At the infirmary where our study was conducted, a group of selected nurses had received training in EBP in order to become an expert resources inside EBP. Educating a selected group of clinicians is in line with suggestions from several researchers who recommend that not all employees need to exist trained to an expert level where they can find, evaluate, implement and generate research [55, 56]. Instead, each department should have some EBP experts to engage the other staff and maintain an EBP approach.

Ciliska [57] suggests that every nurse should at least have an agreement of the purpose and process of EBP, exist able to ask relevant clinical questions, and know who in their surroundings can assist them in answering questions. Information technology is important to brand the entire staff enlightened of EBP and conscious of reflection in practice, likewise equally learning to ask questions. It is the clinician who knows the practice expanse all-time, and who has direct patient contact. The starting point for testify-based exercise is clinical activity. Currently a group of nurses with expertise in EBP announced to be the ones who seek out any answers are bachelor. These nurses are at a prime interface of recognizing clinical problems, having the skills and resources to access the research literature, critically appraising the relevant literature, and translating the findings in a style that forepart-line nurses tin can understand.

A strategy to give staff the take a chance to practise in an evidence-based way without having to have an in-depth competence in the entire process may be to develop procedures, best practices and guidelines that use loftier quality evidence. However, high quality guidelines, procedures and recommendations that include updated inquiry results are not something that just comes to us. At the infirmary where we conducted our study, it was the clinicians who identify a trouble or a dilemma related to a certain procedure, patient information or nursing intervention. For this reason, experts within EBP together with interdisciplinary experts develop evidence-based guidelines, procedures and patient information in evidence-based working groups. The work was organized and supervised past an EBP mentor.

In this written report there was a significant difference between the nurses who took part in bear witness-based working groups and those who did not. Findings from a survey support the idea that mentorship in EBP facilitates the implementation of evidence-based intendance [58]. Polit and Beck [59] stressed the importance of instruction, administrative support, resources, and developing collaborations with potential mentors who can provide guidance and direction in the search for and appraisement of evidence.

Wellness political visions and goals require health staff to have competence in EBP and work in an testify-based mode, simply implementing EBP among nurses in clinical practise is challenging. Although the use of questionnaires replied by individual nurses implies that we measure practice of EBP at the private level, every bit nurses really perform the components of EBP, nosotros do non believe that practicing EBP is a purely private responsibility. As nurses often say that they lack the autonomy to change practice [17, 18], implementing EBP requires a whole system modify implicating individuals, teams and the organization [60].

Effective change management plays a key part facilitating an organizational environment that encourages EBP implementation [61–64]. The lead direction plays a essential office in the technical and facilitative leadership, the organization's policies, procedures, values, established habits, routines, fiscal and human resources and supervision of the clinical and not-clinical processes involved in EBP implementation.

Methodological issues

One weakness of this cross-sectional study is the depression response rate (52%). Possibly a higher response rate could have been achieved with more reminders. In our study, there was no difference in age or education between those who responded and those who did non answer. Nevertheless it is possible that those who answered were more positive towards EBP, and thus, circumspection must exist used in generalizing the findings. There is a risk of receiving socially desirable responses where answers reflect an anticipated social norm, and retrospective self-reports about EBP beliefs and behaviour have been criticized for being biased [65].

The advantage of the questionnaires for the EBP Belief Scale and the EBP Implementation Scale are that they are standardised and have been used in a number of international studies. It is, however, difficult to attain a loftier score on the EBP Implementation Scale. Even Wallen, Mitchell, Menyk et al.'southward exclusive group of participants, who had been through an EBP mentorship program and who would ultimately mentor nurses in EBP, achieved an average score of less than one-half of highest possible score (xl.9 of 72) [43]. And then if an organization in their efforts to implement EBP focuses on a number of selected nurses condign "experts" in EBP, and the rest of the staff being familiar with EBP, the average score of the EBP Implementation Scale for the whole staff is not probable to exist loftier. To score highly all staff would take to carry out many activities related to EBP as part of their routine practice. This may be why the EBP Implementation Scale has mostly been used amidst samples who have a special involvement in EBP or where the effect of EBP interventions are measured.

This survey was conducted at 1 particular hospital at a specific fourth dimension. The nurses who work at this specialist infirmary are known for being competent and at the forefront of their profession. Results from a like study in other Norwegian hospitals may differ.

Conclusion

Findings from this report add to the scientific arena of EBP that nurses are positive towards EBP, but to a bottom extent report practising EBP. There is a relationship between nurses' beliefs towards EBP and the extent to which they report EBP implementation. Further, we see a link between each of the four subscales of the EBP Beliefs Calibration and the EBP Implementation Scale, where beliefs related to knowledge are of the greatest importance for implementation.

Belief in the value of EBP was somewhat higher in the group that had learned about EBP than in the group which had not. In add-on, in that location was a significant difference in those nurses who took function in evidence-based working groups. This may stress the importance of EBP- knowledge and skills, leadership and authoritative support, financial and human resources, and developing collaborations with potential mentors.

While nurses can be taught how to utilize and perform the components of EBP, ongoing support in facilitating an evidence-based practice culture is necessary. It is therefore essential further explore how to all-time to organise the implementation of EBP in the wellness services finer.

References

-

World Health Organisation: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2011, Health Evidence Network,http://world wide web.who.int/evidence/en/,

-

Sackett D, Straus Due south, Richardson Westward, Rosenberg Due west, Haynes R: Evidence based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2000, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone

-

Dawes M, Summerskill Westward, Glasziou P, Cartabellotta A, Martin J, Hopayian One thousand, Porzsolt F, Burls A, Osborne J: 2d international conference of evidence-based wellness care teachers and developers. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Med Educ. 2005, five: i-10.1186/1472-6920-5-1.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing & Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice. 2011, Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Wellness| Lipincott Williams & Wilkins, 2

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout- Overholt East, Mays MZ: The evidence based practice beliefs and implementation scales: psychometric backdrop of two new instruments. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008, 5 (4): 208-216. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00126.x.

-

Thompson C, McCaughan D, Cullum N, Sheldon TA, Mulhall A, Thompson DR: Research information in nurses' clinical controlling: what is useful?. J Adv Nurs. 2001, 36: 376-388. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01985.x.

-

Estabrooks CA, Chong H, Brigidear One thousand, Profetto-McGrath J: Profiling Canadian Nurses' preferred knowledge sources for clinical do. Can J Nurs Res. 2005, 37 (2): 118-141.

-

Estabrooks CA, Rutakumwa W, O'Leary KA, Profetto-McGrath J, Milner M, Levers MJ, Scott-Findlay S: Sources of practice knowledge amongst nurses. Qual Wellness Res. 2005, 15 (4): 460-476. ten.1177/1049732304273702.

-

Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S: Interventions aimed at increasing research apply in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007, ii (1): fifteen-ten.1186/1748-5908-2-15.

-

Gerrish K, Ashworth P, Lacey A, Bailey J: Developing evidence-based exercise: experiences of senior and inferior clinical nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 62: 62-73. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04579.10.

-

Dalheim A, Harthug Southward, Nilsen RM, Nortvedt MW: Factors influencing the evolution of evidence-based exercise among nurses: a self-report survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012, 12: 367-10.1186/1472-6963-12-367.http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/367,

-

Berland A, Gundersen D, Bentsen SB: Evidence based exercise in main care – an explorative study of nurse practitioners in Kingdom of norway. Nurs Educ Pract. 2012, (in press) doi:x.1016/j.nepr.2012.05.002

-

Boström AM, Ehrenberg A, Gustavsson JP, Wallin L: Registered nurses' application of evidence-based exercise: a national survey. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009, 15: 1159-1163. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01316.x.

-

Brown CE, Wickline MA, Glaser D: Nursing exercise, knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers to evidence-based practice at an academic medical centre. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 65 (two): 371-381.

-

Mashiach EM: Implementation of evidence-based nursing practice: nurses' personal and professional person factors?. J Adv Nurs. 2011, 67: 33-42. x.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05488.x.

-

Boström AM, Rudman A, Ehrenberg A, Gustavsson JP, Wallin L: Factors associated with testify-based practice amidst registered nurses in Sweden: a national cross-sectional written report. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2013, xiii: 165-10.1186/1472-6963-13-165.

-

Kajermo KN, Boström AM, Thompson DS, Thompson DS, Alison M, Hutchinson AM, Estabrooks CA, Wallin L: The BARRIERS scale—the barriers to research utilization scale: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2010, 5: 32-10.1186/1748-5908-5-32.

-

Solomons NM, Spross JA: Prove-based exercise barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2010, 19: 109-120.

-

Meijers JM, Janssen MA, Cummings GG, Wallin 50, Estabrooks CA, Halfens YGR: Assessing the relationships between contextual factors and research utilization in nursing: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006, 55 (5): 622-635. x.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03954.x.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey Chiliad, Seers K, Kitson A, McCormack B, Titcen A: An explorian of the factors that influence the implementation of bear witness into practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004, 13: 913-924. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01007.x.

-

Ehrenberg A, Estabrooks CA: Why using research matters. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2004, 31 (2): 62-64. 10.1097/00152192-200403000-00004.

-

Egerod I, Hansen GM: Show-based practice among Danish cardiac nurses: a national survey. J Adv Nurs. 2005, 51 (five): 465-473. ten.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03525.x.

-

Kuuppelomaki M, Tuomi J: Finnish nurses' attitudes towards nursing research and related factors. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005, 42 (2): 187-196. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.001.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt East, Feinstein NF, Sadler LS, Green-Hernandez C: Nurse practitioner educators' perceived knowledge, behavior, and teaching strategies regarding prove-based practise: implications for accelerating the integration of evidence-based practise into graduate programs. J Prof Nurs. 2008, 24 (1): 7-xiii. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.06.023.

-

Yoo JY, Oh EG: Level of behavior, noesis and performance for testify-based practice among nurses experienced in preceptor function. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2012, 18 (2): 202-212. 10.11111/jkana.2012.18.ii.202.

-

Thorsteinsson HS: Icelandic Nurses' beliefs, skills, and resources associated with evidence-based practise and related factors: a national survey. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2013, ten: 67-126. 10.1111/wvn.12006.

-

Estabrooks CA, Floyd JA, Scott-Findlay Southward, O'Leary KA, Gushta M: Private determinants of research utilization: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2003, 43 (5): 506-520. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02748.x.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Feinstein NF, Li H, Wilcox L, Kraus R: Nurses' perceived knowledge, beliefs, skills and needs regarding evidence-based practice: implications for accelerating the image shift. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004, ane (4): 185-193.

-

Varnell G, Haas B, Duke G, Hudson One thousand: Result of an educational intervention on attitudes toward and implementation of prove-based exercise. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008, 5 (4): 172-181. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00124.ten.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt East, Giggleman 1000, Cruz R: Correlates among cerebral beliefs, EBP implementation, organizational culture, cohesion and job satisfaction in evidence-based do mentors from a community infirmary system. Nurs Outlook. 2010, 58: 301-308. 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.06.002.

-

Squires JE, Estabrooks CA, Gustavsson P, Wallin L: Individual determinants of research utilization by nurses: a systematic review update. Implement Sci. 2011, 6: 1-10.1186/1748-5908-half dozen-1.

-

Ajzen I: The theory of planned behavior. Oragan Behav Hum Decis Procedure. 1991, 50: 179-211. ten.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

-

Kyrkjebø JM, Mekki TE, Hanestad BR: Brusk written report: Nursing teaching in Kingdom of norway. J Adv Nurs. 2002, 38 (iii): 296-302. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02179.x.

-

Gifford W, Davies B, Edwards N, Griffin P, Lybanon Five: Managerial leadership for Nurses' Apply of research evidence: an integrative review of the literature. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2007, 4: 126-145. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00095.x.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: EBP Beliefs Scale. 2003, Gilbert, AZ: ARCC llc Publishing

-

Estrada NA, Verran J: Nursing practice environments: strengthening the future of health systems: learning organizations and bear witness-based practice by RNs. Commun Nurs Res. 2007, forty: 187-191.

-

Long EL, Berkett K, McGee S: Promotion of safe outcomes: incorporating evidence into policies and procedures. Nurs Clin North Am. 2009, 44 (i): 57-70. 10.1016/j.cnur.2008.ten.013.

-

Estrada North: Exploring perceptions of a learning organisation by RNs and human relationship to EBP behavior and implementation in the acute care setting. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2009, 6 (iv): 200-209. x.1111/j.1741-6787.2009.00161.10.

-

Mariano KD, Caley LM, Escherberger L, Woloszyn A, Volker P, Leonard ML, Tung Y: Building evidence- based practice with staff nurses through mentoring. J Neonatal Nurs. 2009, 15: 81-87. 10.1016/j.jnn.2009.01.005.

-

Melnyk BM, Bullock T, McGrath J, Jacobson D, Kelly S, Baba 50: Translating the testify-based NICU COPE program for parents of premature infants into clinical practice. Impact on Nurses' testify- based practice and lessons learned. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2010, 24 (ane): 74-eighty. 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181ce314b.

-

Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO, Levesque DA: A transtheoretical approach to changing organizations. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2001, 28 (4): 247-261.

-

Levin RF, Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Barnes M, Vetter MJ: Fostering evidence-based practice to meliorate nurse and cost outcomes in a community health setting: a pilot test of the advancing research and clinical practice through close collaboration model. Nurs Adm Q. 2011, 35: 21-33. x.1097/NAQ.0b013e31820320ff.

-

Wallen GR, Mitchell SA, Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E, Miller-Davis C, Yates J, Hastings C: Implementing evidence-based practice: effectiveness of a structured multifaceted mentorship programme. J Adv Nurs. 2010, 66 (12): 2761-2771. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05442.10.

-

Lynch SH: Nurses' Behavior nearly and Use of prove-based practice. Doctoral Dissertations Paper. 2012, University of Connecticut, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 3520427

-

Polit DF, Beck CT: Nursing Research – Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 2008, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

-

Sciarra East: Does periodical club membership empower exercise?. Nurs Manag. 2011, 42 (i): 17-eighteen. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000390983.45839.ff.

-

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Immature JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O'BrienMA JM, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: furnishings on professional do and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, Consequence half-dozen (Art. No): CD000259-doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3

-

Nylenna M, Eiring O, Strand One thousand, Røttingen J: Wiring a nation: putting noesis into activity. Lancet. 2010, 375 (twenty): 1048-1051.

-

Novak D, Doodley S, Clark R: Best practices: agreement nurses perspectives. J Nurs Adm. 2008, 38 (10): 448-453. 10.1097/01.NNA.0000338153.17977.83.

-

Gale BV, Schaffer MA: Organizational readiness for prove-based practice. J Nurs Adm. 2009, 39 (ii): 91-97. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318195a48d.

-

Nagy Southward, Lumby J, McKinley S, Macfarlane C: Nurses' beliefs about the conditions that hinder or back up bear witness-based nursing. Int J Nurs Pract. 2001, seven (5): 314-321. 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2001.00284.10.

-

Wallin LA, Bostrøm M, Wikblad K, Ewald U: Substaining ability in Chanching clinical practice promotes evidence-based nursing care. J Adv Nurs. 2003, 41 (five): 509-518. x.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02574.x.

-

Hutchinson AM, Johnston Fifty: Beyond the BARRIERS calibration - normally reported barriers to inquiry use. J Nurs Admin. 2006, 36 (4): 189-199. ten.1097/00005110-200604000-00008.

-

French B: Contextual factors influencing research use in nursing. Wordviews Evid Based Nurs. 2005, 2 (4): 172-183. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2005.00034.x.

-

Straus S, Haynes B: Managing show-based knowledge: the need for reliable, relevant and readable resources. Tin can Med Assoc J. 2009, 180 (ix): 942-945. ten.1503/cmaj.081697.

-

Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Haynes RB: Practitioners of show based care. Not all clinicians demand to appraise evidence from scratch but all demand some skills. Br Med J. 2000, 320: 954-955. x.1136/bmj.320.7240.954.

-

Ciliska D: Testify-based nursing: how far have we come? What's next?. Evid Based Nurs. 2006, ix: 38-40. x.1136/ebn.9.2.38.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt East: Putting inquiry into exercise. Reflect Nurs Leadership. 2002, 28 (ii): 22-25. 45

-

Polit DF, Beck CT: Nursing Research Generating and Assessing Prove for Nursing Practice. 2007, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

-

Rycroft- Malone J: Testify-informed practice: from individual to context. J Nurs Manag. 2008, 16: 404-408. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00859.10.

-

Aarons A, Fettes D, Flores L, Sommerfeld D: Evidence-based practice implementation and staff emotional exhaustion in children'due south services. Behav Res Ther. 2009, 47 (11): 954-960. ten.1016/j.brat.2009.07.006.

-

Proctor KE, Fedoravicius N, Hovmand P, Knudsen JK, Perron B, Rosen A: Implementation of show-based practice in community behavioral health: Agency managing director perspectives. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Wellness Sev Res. 2007, 34 (five): 479-488. 10.1007/s10488-007-0129-8.

-

Barwick M, Kimber Yard, Fearing G: Shifting sands: a case study of procedure change in scaling up for testify-based practice. Int J Knowl Civilisation Alter Manag. 2011, 10 (8): 97-114.

-

Lawler J, Bilson South: Towards a more reflexive enquiry aware practice: the influence and potential of professional and team culture. Soc Work Soc Sci Rev. 2004, 11 (1): 52-69. 10.1921/17466105.11.one.52.

-

Shaneyfelt T, Baum KD, Bell D, Feldstein D, Houston TK, Kaatz S, Whelan C, Green 1000: Instruments for evaluating teaching in evidence-based practice: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2006, 296: 1116-1127. 10.1001/jama.296.nine.1116.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this newspaper tin can exist accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6955/13/viii/prepub

Acknowledgement

The authors would similar give thanks the nurses who contributed to this study and the contacts at each unit that were responsible for handing out and collecting the questionnaires, as well as handing out data letters, consent forms and respond envelopes.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KS performed this study with supervision from NRO and MWN. MWN and NRO contributed to the formulation and design of this study. KS collected the data. KS and BE contributed to the data assay and interpretation of data. KS was responsible for the drafting of the manuscript. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and made a substantive contribution to revising the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stokke, K., Olsen, N.R., Espehaug, B. et al. Evidence based practice beliefs and implementation amidst nurses: a cross-sectional report. BMC Nurs xiii, eight (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-thirteen-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-xiii-eight

Keywords

- Evidence-based practice

- Beliefs

- Behaviour

- Implementation

- Nurses

- Survey

Source: https://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6955-13-8

Post a Comment for "What Is the Nurse's Responsibility When Ebp and Patient and Family Practice Do Not Match?"